Ollauri in the 20s: a legendary dinner

Joaquín Belda enjoyed a fabulous evening at the wine caves

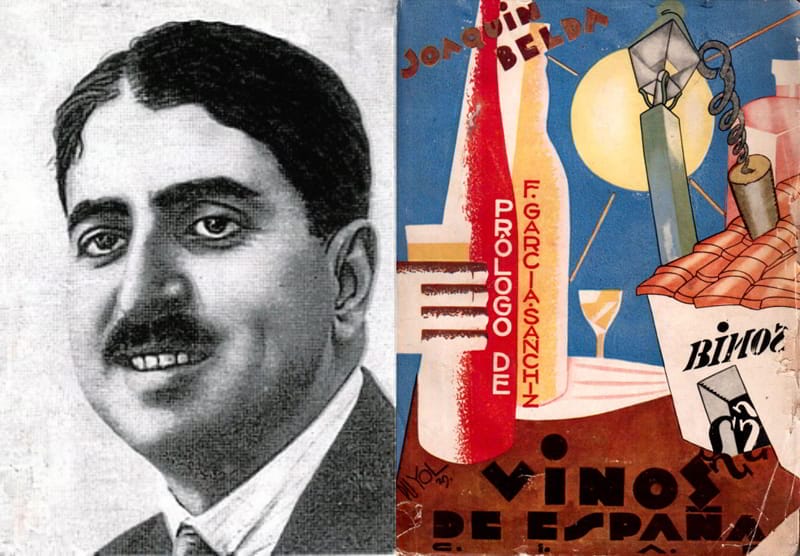

At the end of the 1920s, journalist and writer Joaquín Belda (very popular at the time for its satyrical writings) was engrossed in writing his book Vinos de España, published in 1929. He travelled across the most varied wine regions to gather information. Naturally, he spent a great deal of time and effort in the wines of Rioja, a region which was then getting ready to become the first denomination of origin in Spain.

During one of his trips to Rioja, Belda spent some time at Paternina, predecessor of our own bodega Conde de los Andes. Over several days, he had the chance to taste the brand's renowned wines, visit the cellars in Ollauri and share many moments with two unforgettable characters: Joaquín Herrero de la Riva, owner of the winery at that time, and winemaker Etienne Labatut.

With his lively, humorous style, Belda describes several occasions around the same bottles that still rest in our cellars. His account of the memorable dinner-tasting held in honour of Belda's group at the cellars in Ollauri is particularly interesting. After reading these pages "a passage is published below" we still seem to hear in the cellars echoes of the laughter and chatter of Belda and his friends. It would have been great to be among them.

One of my fondest memories from the social tertulia at Café Los Leones is making Joaquín Herrero de la Riva's acquaintance.

This pleasant character, with a priestlike face and gentlemanly manners, is an institution in Logroño and an intelligent, pleasant man everywhere. Owner of the first bank in Logroño, he is one of the main shareholders of Sociedad "Federico Paternina". Given his enormous love of viticulture, in which he is extremely well-versed, he is much more than just a shareholder: he is, simply, the soul of the business.

Fifteen minutes into our acquaintance, we found ourselves at the dining-room of his flat in Bretón de los Herreros street in the company of other friends and five bottles of Paternina; three reds and two whites. The reds were: one Banda Azul, vintage 1924; one Banda Roja, 1923; and one with wire-netting in its fifth year. The whites were: one cepa Sauternes, 1921; and a cepa Rhin, 1920.

As it is clear, we were not alone.

The conversation with Joaquín Herrero de la Riva was as good as the wines he offered us. And that is quite something! Tasting such nectars while listening to his explanations doubled the flavour. Each Rioja house has its own trait: this house's is what we could call the totality trait; there is not a single element of a fine Rioja wine that fails to be present in his portfolio.

The day after this preparatory session, we were driven to Ollauri in three automobiles. The plan for the night included a visit to the cellars of Federico Paternina followed by dinner. What a great programme!

Ollauri is a small village with many slopes that is located opposite Haro; it was almost dark when we arrived there.

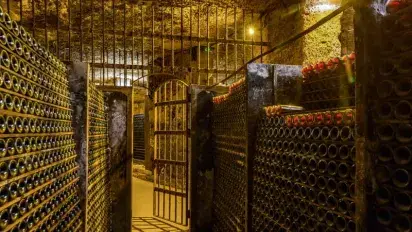

The Paternina cellars are caves in almost all of their extension; but these caves and galleries were opened with pick and shovel on the bedrock of the mountain. No aromas are lost in those underground spaces; it could be said that the evaporated ethers of wine, having no chance to escape, return to the wine, concentrating and bolstering that special bouquet, which is one of its charms.

From the halls of the Ollauri cellars, one felt surrounded by the intense aroma of the finest wines, which persisted until well after going outdoors.

We spent about one hour "no exaggeration" tasting different types and styles of wines. Some of the 15 dinner guests who had travelled with us from Logroño were eating walnuts to prepare the palate for a more perfect tasting. There were rounds of applause and cheers beneath a cask containing a cepa Rhin wine.

Accompanying us on the tour was the house's cellar master, a blond and tanned Frenchman called Étienne Labatut (a Bordelais who knows more about wine than the inventor of the vineyard). By the way, I would like to praise the skills of the Spanish cellar masters, seasoned workers whose names are never seen on the labels of the bottles but whose expertise and craft are essential for us to drink the fine wines that, thanks to the Lord and to them, are available in Spain. I salute all the cellar masters who have offered me a drink on this journey.

Monsieur Labatut was cellar master at the famous Maison Calvet in Bordeaux; Joaquín Herrero brought him from this French city. In 1920 Labatut was awarded the top prize at the École Philomathique in the Gironde capital; before that he fought in the war. This son of Bordelais grape growers spent 43 months at the front as a member of the 7th Colonial Infantry Regiment. Wounded twice, he was awarded three citations, the Military Medal, the Cross of War and was promoted to sub-officer on July 27th, 1917.

He is a hero and a very intelligent man. The French greatly value their wine, to the point of not hesitating to place the epic heroes of the nation under his care.

Joaquín Herrero and Étienne Labatut are the two pillars at Paternina; they meet daily and share a friendship. Listening to them talk about wine means storing science.

After an hour tasting wines, dinner was served. The table was plainly laid in a room at the bodega, not far from the long rows of casks. Teniers would have had nothing to say about the setting.

Giving an account of what was eaten and drunk would require a great deal of space. To accompany the string of plates, 14 red and white wines made by the Paternina estate were served. Should I mention that each of the diners tried everything that was on the table and many of us went beyond just having a taste?

I was sitting next to Étienne Labatut. On one occasion, as the contents of a glass of Cosecha Vieja red passed through my lips, I mentioned the old pun, so popular in France, used when one of the drinkers is called Étienne:

"A la tienne, Étienne;" and my apologies for my over-familiar language, I hastened to add.

"It dzoesn't matterg, it dzoesn't matterg" he replied, with the best of his smiles.

And as two diners lit up a cigarette (we were in the midst of our meal) the cellar master amicably complained:

"Mais, non! Don't smoke now"

"Well, well; don't be upset".

And they disposed of their cigarettes.

It was midnight by the time we ventured outside to the streets of the village. It wasn't cold "if it was, we didn't notice". And it was on this night, during the visit to the cellars in Ollauri, that I became fully aware of the huge gulf between good wine and mediocre or bad wine.

Some 15-20 of us had been drinking for about five hours without interruption at the Paternina cellars; in truth, we had all eaten well and in abundance, but the amount of wine we imbibed was nothing short of fabulous.

And not one of us was even excited nor drunk; nobody staggered or wavered in the dark of the night, along the stone-covered slope that led us to the place where the cars were waiting. We were indeed jolly and cheerful, but none of us had crossed the line separating a drinker from a drunk.

To Muerza, well-known for his delicious tinned asparagus, by now famous worldwide, and a member of the party that night, I said:

"We are as canned as those asparagus of yours".

"And more soaked too", he replied.

You may also be interested in: